When most people pass away, their stories, told in their own words, are lost – unless somebody thinks to record them.

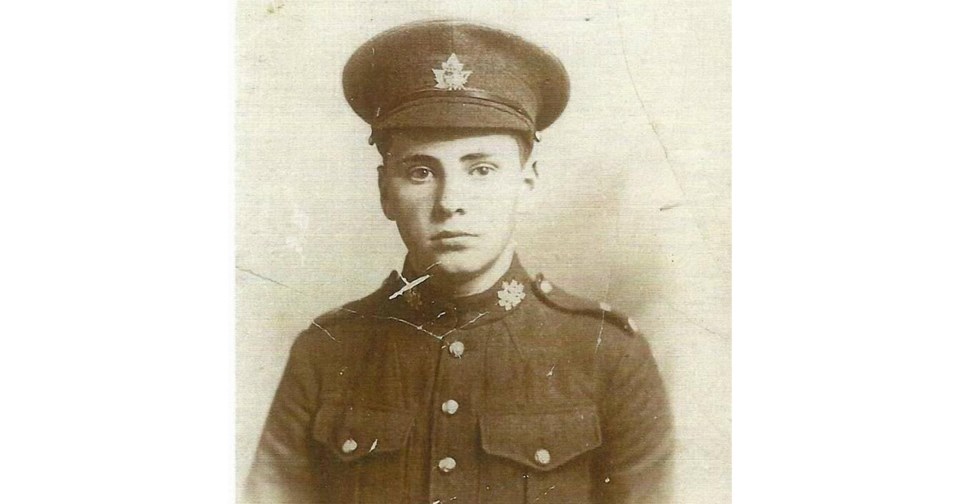

That was the case for First World War veteran Daniel Alexander Dewar, who had his story recorded by his granddaughter Marion Clements knowing how valuable it could be.

The recording was donated by Jeanne Hosaluk and transcribed by Sarah Gibbs.

1917

Dewar’s story starts with his training, training that he called “ordinary” at Valcartier.

“Just ordinary training, marching and musketry [when] we shot at the range,” Dewar said into a recording. “[It] was one of the best shooting ranges in the world, at Valcartier, [it was] a level plain. It was about three miles across and 11. So we had done target practice and physical training and squad drills and all that at Valcartier. And [it] was a great sea of tents.”

Training wasn’t always easy. That day in particular they were being inspected by a man named Sam Hughes, and Hughes picked a bad day for it.

“The day he came there was 25,000 soldiers on the parade and a very hot day, that’s the day we were carrying them away on stretchers, they’d topple over and get overcome with the heat. And we stayed there ‘til the 13th of June. We left on the 13th of June and went back to Halifax and got in the boat and went overseas.”

He would continue training in Europe until April.

“About the first of April it looked like the Germans were winning the war,” Dewar said. “They put on a big drive in France and we were all gathered up and shipped overseas, shipped over to France across the channel. And I was seasick all the way across the English Channel. We got to France, we landed in Boulonge and we had supper there and then we got, at dark, in the little train... and from Boulogne we went to Etaples. And at Etaples we, I think it was at Friday we got there, on Saturday we had the medical examination, Sunday we went church parade and after we had dinner.”

After that he was told to check his equipment and ammo before heading out to a small village he would stay for two nights before heading out in the rain.

“It was very dark and we were going up towards the front and you could see the guns flashing [in the distance] like lightning I didn’t know what I was getting into.”

“That’s where we stayed and then we used to go out each day to dig trenches in the vicinity of [Reims] and Vimy Ridge and Hill 70,” Dewar said. “We dug trenches there for a month or more and worked every day and came back at night and we had about five or six feet of trench to dig at three feet deep and three feet wide at the top and two feet wide at the bottom. And built a parapet to put your elbows on and shoot over the dirt.”

From there he went to Aire, beside a canal that the Germans bombed every night.

“Scared us pretty bad but none of us got hurt and then from there we went to Aubin Saint Vaast and that was a nice little village and [had] a river run by it,” Dewar said. “We were quartered there in barns and different places. In France, the farmers they all live in villages.”

He slept in a barn there with the other men until August.

“The big drive started and on the 8th of August [there was the battle of Amiens] they sent us out there to join their battalion.”

They landed in Amiens at midnight and slept in a field until morning.

“In the morning we had breakfast [at the church of Amiens] and then we started walking across the battlefield to catch up to the battalions. Once we left where we were, everything was desolation. There was big fields of wheat all tramped down and dead Germans laying here and there in the fields and one place where they used cavalry, where there was a cavalry charge, there were dead horses all over the place. We picked up lots of souvenirs like cavalry swords and one of the fellas said ‘this must be the abomination that makes us desolate spoken by Daniel the prophet.’”

They caught up to their battalion in the evening where they were drafted to different companies and platoons.

“And then we went in through the line there,” Dewar said. “For four of five days and that was the old 1916 fighting since the start of the war...in weeds and nasty barbed wire and trenches that you didn’t know where they were, but anyway we stayed there for about a week.”

After that they headed out, eventually reaching a place near Arras.

“And we landed at the rest camp near Arras and we had a bath and picked the lice and whatnot. The Battle of Arras was to start on Sunday morning.”

It was to start Sunday morning, but his general decided to wait another day.

“We get up to the front some time about 12 or one o’clock and into dugouts and waited there until the morning,” Dewar said. “At three o’clock in the morning and the ground fairly shook and then we were routed out of our dugouts and lined up in artillery formation, all scattered out, section here, and one over here, so that there wouldn’t be too many in a crowd that would be hit with shells, have too many casualties. We advanced behind the sixth brigade, we were the fifth brigade, and the sixth brigade was in front of us. So we went I guess several miles that day and then we stopped and then the next night I was picked to go out on a [ration march] and bring back and meet the wagons that brought the supplies.”

This brought him to the Second Battle of Arras, with the 26th Battalion.

“And we were away all night, this here little group, you know, this detachment. And we didn’t get back about six o’clock in the morning. The roads were crowded. There were soldiers coming up and guns and we figured there was something big for the next day. So when we got back we were told we were to pack up and move up to the front, we were to go over the top at 10 o’clock.”

It was a beautiful August day, and their officer in charge lined them up shaking each one of their hands.

“And then the guns opened up, oh, in about 15 minutes before we were to go over. At first, they shoot over your head you know, the artillery, and they turned them onto the barbed wire first and the infantry falls behind and the shells are dropping in front of them but they keep behind, it’s all timed. And we get all scattered out and we’re running as fast as we could and make sure we’re in the right places and jump into shell holes for shelter. And so we got up close to the Germans and this little French man and me, we were kind of ahead of the rest as they told us before we left to get there quick. And in the last bit of rush we made it. There was a hole, I could see in the weeds and I could see some German helmets around a machine gun, I thought. And then we dived into this here shell hole and in a few minutes there was a little white flag waved on a stick. So we just got up and walked right up to them and they were really glad to see us.”

The German officer had been shot.

“He was laying on the ground beyond the trench and I guess that’s why they gave themselves up so easy. And then from there we advanced, I guess, oh, must have been three miles. And we met several more bunches of Germans that had give themselves up and met them on the way coming out back and we kept [on until] we came to a hill, a steep little hill. And right near the top of that we had to wait there while the shells were coming both ways. Then we [advanced] over the hill after a while and I got in a shell hole with a big lumberjack from New Brunswick. And the shells were bursting all around us and we said ‘let’s get the heck out of here,’ and away we went. We saw some dirt [dug] up, mounds of dirt over to our left a little bit and in front and we ran as hard as we could for that. And we got there and it was a German gun emplacement and the gun was there but the Germans had left.”

From there, at around 2 pm, their officer told them to stay where they are, that they were doing alright. That night he would need to go on a ration trip.

“We were awake quite a while and we’d seen dead Germans lying along the road and some of our fellas laying in the moonlight with their equipment on where they’d fallen. And we got back in the morning and then we were told we were going over the top at 11 o’clock. So we went over again at 11 o’clock but we didn’t get far, we had too many casualties. Our colonel was killed and quite a few of the officers... in our platoon we had four sections and this time we just had two left, two sections.”

Later that night he was relieved after the first division took over, allowing him to go back to the rest camp until September where they moved to Canal du Nord.

“There we had to cross to sunken road and there was three nice fat horses that had been killed a few months before that [laying on] this road. And that that time, this was territory that had been captured from the Germans.”

That image hung in his head the next day.

“So the next day, I was detailed to go to pick up the rations, there’s a dinner, you know, [and went] down to where the cooks were. And when we go to the road, the horses were gone, there wasn’t a trace of a horse or anything, [they had] been gone, but the cooks had a lovely roast beef and brown gravy and mashed potatoes and I couldn’t eat a bite of it [because] all I could think about was those horses.”

They were there for about a week before they went sent to take up positions.

“The corporal and I, we stayed together, and we squared out a shell hole and we made it about that deep and [cut] the corners out pinned down with little sticks,” Dewar said. “And we stayed there and at nighttime you could get up and walk around and the Germans, they would be putting up star shells and, oh, different signal lights.”

At daytime Dewar could do nothing but stay still.

“Sometimes the planes would just swoop down and, I guess, look and see who was there and they shelled the place every once in a while, the shells were coming pretty close, sometimes spent pieces would cut through the rubber sheets.”

After a few days he was relieved, with another section taking their place. Nobody was hurt. While they were resting two of the soldiers volunteered to take first watch in case there to watch for an attack.

“And so they were up at the top of the steps, in the doorway, cleaning their rifles, and big shell [went out] on the road, just killed the two of them. The blast threw them back and [partway] down the steps. And their bodies were just riddled...and we carried them out and left them side by side out on the road and cleaned the place up.”

Their officer said he didn’t think it was a safe place, but they responded they didn’t think they were safe anywhere. So they stayed and tried to get some sleep. That was until they were attacked again.

“And a little piece hit me in the knee and the corporal, he got three chucks [and we had] to get a stretcher for him and I was hopping around on one foot and I hopped out of the place [and the fellow outside] and he says, ‘what’s the matter with you? You hit?’, And he took a look and said ‘oh boy, you got a dandy, you’re for England.’ I looked down and all I could see was two holes in my pants.”

“So he helped me down into the dugout and he cut the pants away and poured some iodine in it and [tied] a bandage on it and helped me down to where the doctor was. [But] the doctor was so busy, he said, ‘just leave it the way it is.’”

Soon Red Cross was picking up the wounded and carrying them back to the pill box.

“A big place made out of cement, you know, the Germans had built. And [they] were taking them in there [where] it was sheltered and this medical man, he asked me if I could walk and I tried and I couldn’t my leg would just go out. So he put me on his back... and away he went... I took a look back. The other two poor fellows were laying there on the road, side by side with their arms folded and I thought, ‘I must be lucky.’”